Developing and deploying an HTTP/3 API in Go

Published on 2025/01/14

Introduction

While the HTTP/3 protocol is already used by cloud giants for delivering web content, this article explores how it can be leveraged in the case of an API.

This new version of the HTTP protocol has been designed to provide better performance to the applications and their users, by providing both a large compatibility with the previous versions, and at the same time introducing a radical change by using a new transport layer. As HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 performance is not too bad, we will ask ourselves what better means.

A significant part of this article is intended to provide the technical information that is needed to understand how HTTP/3 can be applied in various situations. As we will see concerning the API, the development part is almost not specific to the new version, obviously as long as we stick to the features existing prior to version 3, however the deployment is rather challenging, we will focus on self-hosting for the later.

The use case is based on a real application and involves a mockup in Go. For the French readers, this is mainly the writing of a talk given at the Capitole du Libre conference, on 2024/11/16.

Very interesting links are provided at the bottom of this page for additional information.

HTTP/3 compatibility and disruption

HTTP

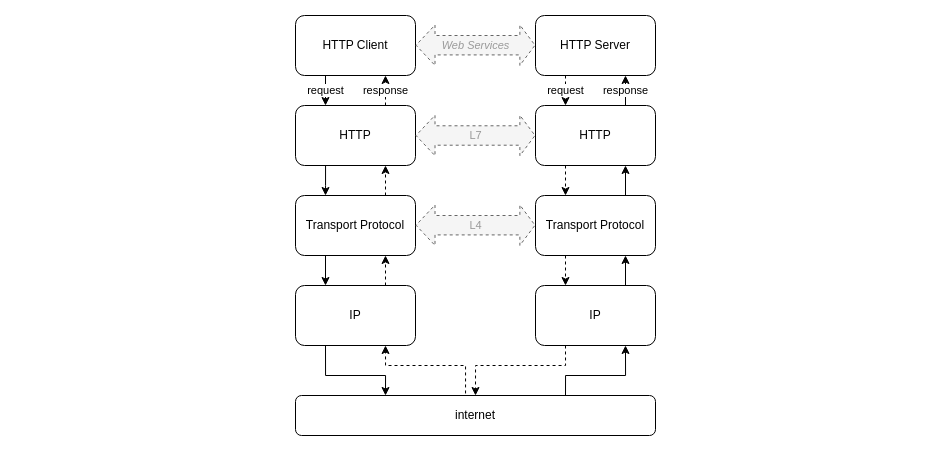

Referring to the OSI model, the HTTP protocol is a Layer 7 "application" protocol, providing services to Web Services which are either clients (such as a Firefox Web Browser) or servers (such as an Apache Web Server), and relying on a Layer 4 "transport" services, which are responsible to transport data between two machines connected to the internet. Internet protocols use a shortcut between Layer 7 and Layer 4.

The HTTP protocol defines various entities very well known by the web developers such as:

- requests, URLs, responses

- methods: GET, POST...

- headers, body...

Whatever the version is: 1.1, 2 or 3, the HTTP protocol doesn't change the role of those entities, but only adds new ways to use them, for instance enabling the server to push data in versions 2 and 3. The HTTP protocol can also leverage some new features of the transport protocol while they are introduced, for instance HTTP/1.1 was needed to take benefit of the TCP keepalive new feature in the 90's.

Talking about the transport protocol, that's where the disruption of HTTP/3 occurs.

TCP, UDP and QUIC

The Internet defines the two widely used transport protocols: TCP and UDP.

TCP provides to the L7 protocols some features that are almost always wanted such as reliability: no data is lost, ordering: data is received in sequence, and congestion control: client and server make a wise use of the bandwidth and the network latency.

UDP on the other hand is very efficient as being very close to the IP protocol (L3 network layer) that sends packets between interconnected machines and routers. It merely adds the end-to-end data delivery, but misses the features mentioned above. It is mainly used on LAN but also for simple L7 protocols such as DNS.

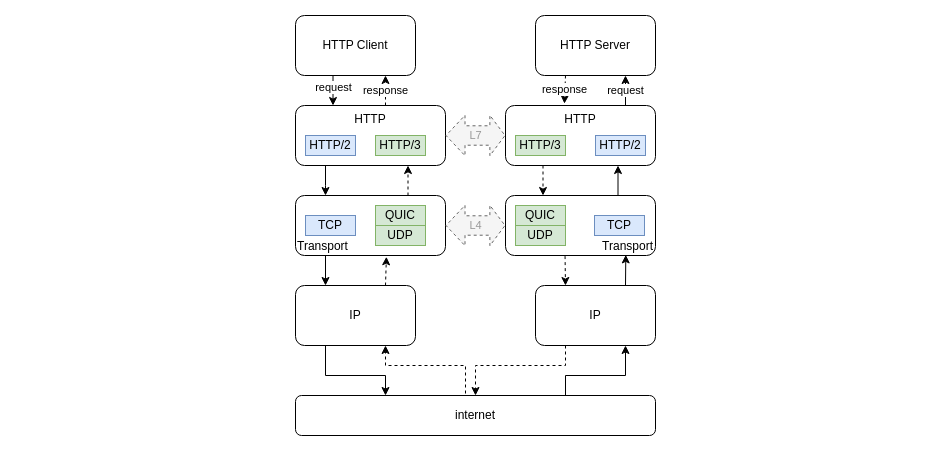

The design of HTTP/3 relies on an additional transport protocol named QUIC, that sits upon UDP to provide L7 protocols a transport that is reliable, delivers data in sequence and controls congestion. From the HTTP/3 perspective, the transport protocol is QUIC, but it actually relies itself on UDP for any data transport.

Is HTTP/3 confidential?

Talking about HTTP/3 in 2025 reminds us that QUIC has been developed by Google starting in 2012, an IETF draft was published in 2015. HTTP/3 has been implemented in Chrome in 2019 and in Firefox and Chromium in 2021. Cloud providers have been implementing it on their private infrastructures since 2017.

It may come as a surprise that HTTP/3 is not more popular among the IT communities, for instance Google trends show around ten times more interest to HTTP/2 compared to HTTP/3. The major Open Source communities apart from Mozilla's Firefox yet don't pay much attention to it. For instance Apache ignores it and Nginx implements it for incoming flows only and with experimental support.

So we could consider HTTP/3 and QUIC as being merely the business of major Cloud providers for delivering web and multimedia content in the most efficient way. Hopefully will the next parts give a little bit more context to better understand this unusual and potentially harmful situation.

Rationale for HTTP/3

The evolution of TCP/IP and TLS

TCP/IP was designed in the 70's and standardized in 1980. It has successfully enabled huge network technology and usage changes, among which bandwidth increase and latency decrease, the World Wide Web deployment in the 90's and eventually the Web 2.0 deployment with related resource usage. Confidentiality by using SSL and then TLS have been generalized.

Technically speaking, as its name implies, TLS appears to L7 protocols as a secured transport, sitting upon a L4 protocol such as TCP.

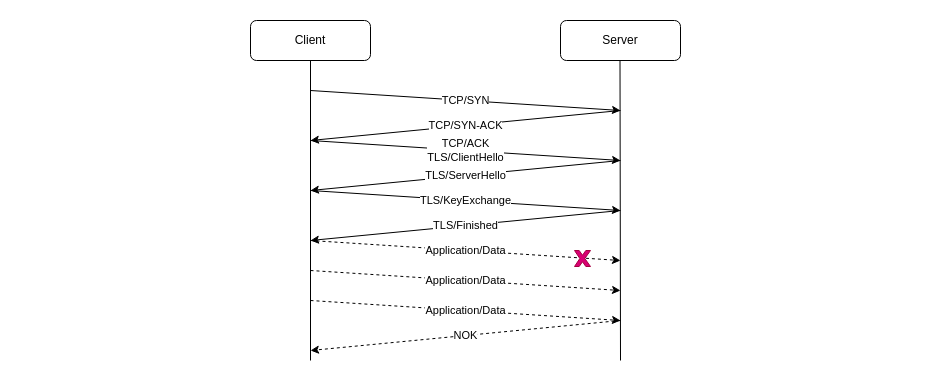

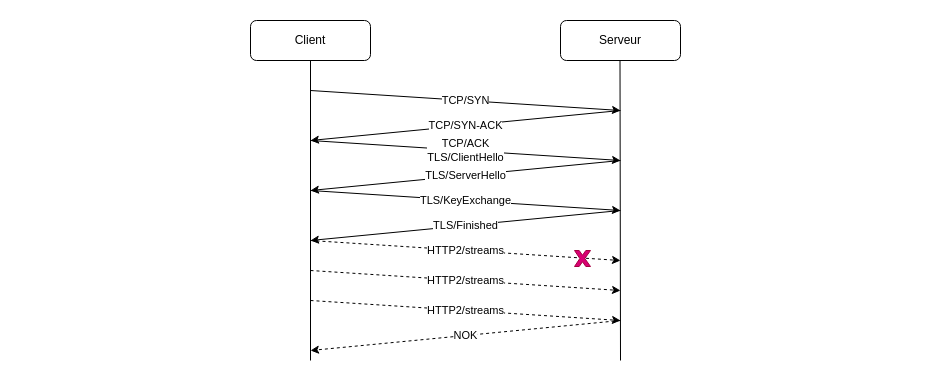

Here is how a TCP and related TLS security connections take place between two peers wanting to communicate:

TCP requires a 3 way handshake, after which TLS adds 2 round-trip security-related data exchanges. Only then can the application data exchange occur. The vertical line being the axis of time, and network latency on the WAN being several dozens of milliseconds, application payload exchange will demonstrate delays of a few tenths of a second.

TCP head-of-line blocking

The head-of-line (HOL) blocking takes place when network errors occur: as TCP tries to make an efficient use of network resources, several packets will typically be sent before the peer detects the error and is able to notify the sender. The data that has been sent is discarded and need to be sent again. In the end, error detection and data retransmission are even more painful due to WAN network latency.

A few optimizations

To be noted:

- TLS is able to manage session resumption, thus reducing the number of round-trips needed when two peers have already communicated and kept the history

- TLS/1.3 reduces the number of round-trips to one

The evolution of HTTP

HTTP takes direct benefit from successive optimizations of the transport protocol.

The venerable HTTP/1.1 implemented TCP keepalive in the late 90's and is still widely used today.

HTTP/2 appeared in 2015, so somewhat in parallel with HTTP/3, with several important features, among which requests multiplexing and prioritization, server push and headers compression.

Multiplexing requests is supposed to limit the effect of HOL blocking at the application level. However, they are not (yet) widely implemented, moreover HOL blocking still occurs at the TCP level.

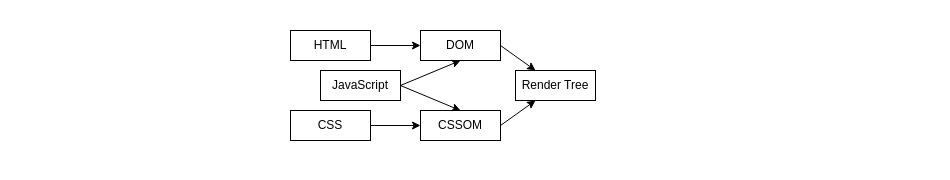

Concerning the prioritization of requests, it is not easy for a web browser to apply general hints that would enable at least initial information to be displayed to the user:

On the schema above, the three kinds of resources depend on each other, as soon as JavaScript reads the CSSOM before updating the DOM. Moreover, web resources packaging used to aggregate CSS and JavaScript in large compressed chunks, for efficient handling of network errors with HTTP/1.1, while HTTP/2 would dictate to keep them as small independent resources. However deployments generally must honour both versions of the protocol as supported by browsers or infrastructure, thus preventing best optimization.

Given all those restrictions and limitations, the benefits of HTTP/2 on poor quality networks is mitigated.

QUIC to the rescue

Comparing QUIC to TCP

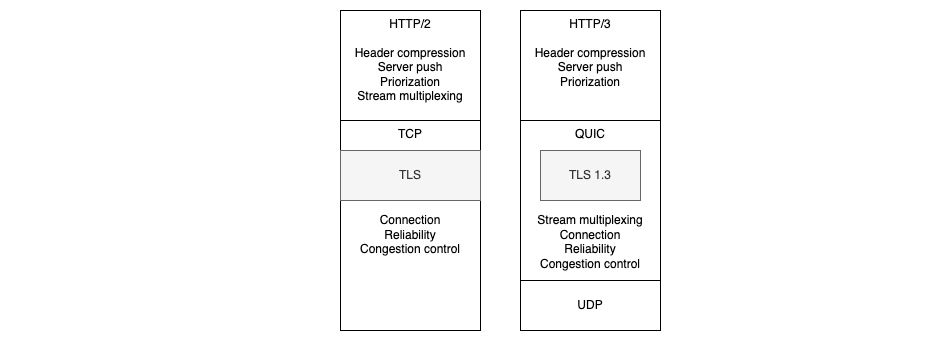

As said before, QUIC provides HTTP/3 with transport services that are equivalent to their TCP counterpart:

As we can see, QUIC provides even more with the definition of streams at the transport layer that can be multiplexed. Thus HTTP/3 will be able to provide the same features as HTTP/2 did, without having to implement multiplexing by itself.

What is less apparent on this diagram is that QUIC can also directly leverage unreliable UDP services, useful when performance and near real time matter but not reliability: for instance in the case of audio or video streams where a few frames may be lost without consequence.

QUIC uses TLS/1.3 and does not allow unencrypted connections. It becomes by itself a secured transport and integrates TLS rather for its encryption services than as a transport service. It encrypts even more data than TLS over TCP (protocol headers) making the confidentiality better.

QUIC performance

QUIC creates new connections with a single RTT, or even 0-RTT with some security constraints.

QUIC multiplexes data from different streams by aggregating it dynamically into a single frame, a frame being generally the same as an UDP datagram or an IP packet, protocol headers not being considered. This enables better behavior in the case of network errors, as their detection occurs more rapidly and corresponding data retransmission is focused on the lost part. The cost to pay for that is more memory on both sides.

At some point HOL blocking still occurs but it is fixed faster and more efficiently.

Other QUIC characteristics

QUIC is implemented as a library, like TLS is, rather than in the kernel of the Operating Systems, as TCP and UDP are. The consequence is that security must be addressed very seriously because vulnerabilities in a library are more likely to occur. On the other hand, fixes or new protocol experiments, for instance regarding congestion control algorithms, may apply more easily than with a protocol implemented in the kernel.

QUIC also enables connection migration, for instance enabling a user or a client application to disconnect from a network and connect to another, without loosing the existing logical resources allocated.

As mentioned before, QUIC consumes more resources, mainly memory, making it inadequate for some embedded devices, and requiring more expensive hardware for network appliances. But as it provides better performance and less bandwidth waste, this has to be balanced.

QUIC for HTTP/3

HTTP/3 basically offers the same services as HTTP/2 does, with the gains provided by QUIC: faster connection setup and faster recovery when network issues occur. Moreover, the streams multiplexing being handled at the transport level and on both directions of the connection, more reactivity in data exchanges may be provided without waste of bandwidth.

HTTP/3 also leverages QUIC disruptive features with interesting extensions like WebTransport over HTTP/3. This extension provides a transport protocol abstraction to peers over HTTP, and, as QUIC, this transport may be both reliable or not reliable for better efficiency.

Using HTTP/3 for APIs

Is it worth using HTTP/3 for implementing APIs? Before looking at the hosting topics, we must understand if the benefits of the new protocol will be significant.

Browser client API

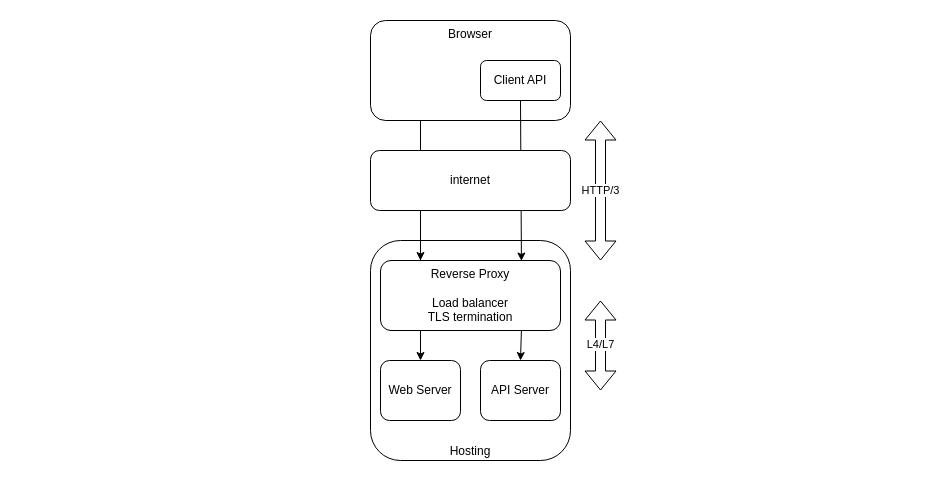

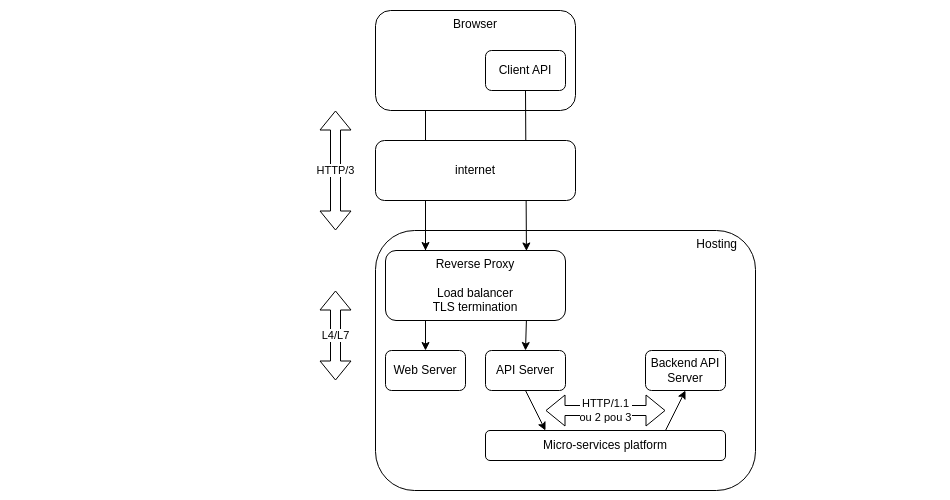

The case where the API requests come from a script loaded by the browser is specific, because the HTTP/3 connection is managed by the later:

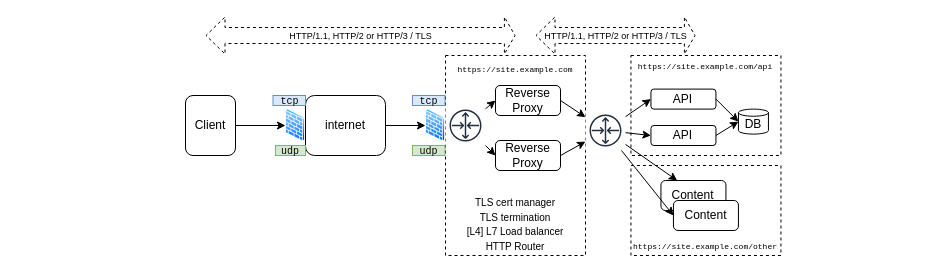

We typically host Web resources and Web APIs on separate platforms behind some kind of reverse proxy (reverse simply meaning it sits in front of the servers and not in front of the clients internet access). This schema is for sure specific to self-hosting, while different cloud providers would propose different and specific hosting options, but the conclusion of this section would still apply.

So in that case, the HTTP/3 connection is established between the browser and the reverse proxy, using TCP keepalive, which means that the API will be able to share the connection with other resources managed by the browser. We benefit here of the performance enhancements provided on WAN by HTTP/3, but at this point this is not specific to the API implementation.

Indeed, the connection to the API Server is handled by the reverse proxy, relying on data-center network infrastructure, meaning high bandwidth and low latency. Of course the API could be remote to the reverse proxy, and in that case the following sections would better apply. But in the more frequent co-location scenario occurrence, no real performance gains will be observed by using HTTP/3, except for specific cases where we want a high level of reactivity, or obviously when we want to use HTTP/3 specific features.

Backend API

For the same reason but also the same exceptions, a backend API won't generally benefit from HTTP/3.

On the previous schema, the backend API is called by a frontend API which, in case they both share the same datacenter network, won't generally gain any performance when using HTTP/3.

Remote machine-to-machine API

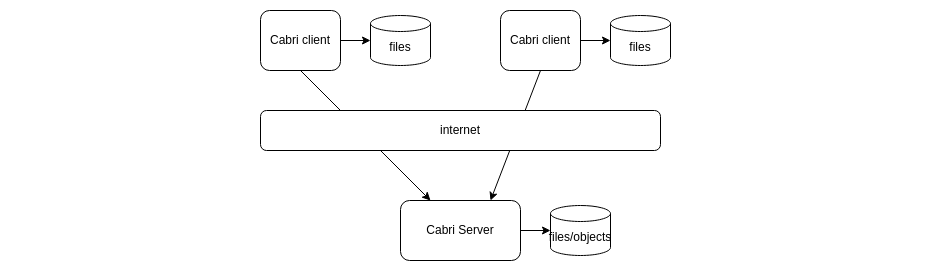

Remote machine-to-machine API calls are not so frequent, but HTTP ability to deal with WAN latencies is also appreciated for such architectures. In my case the need occurred while deploying the Cabri tool for remote files synchronization:

Cabri provides among others the same kind of service as rsync does, but over HTTP instead of SSH. The cabri internal HTTP API usage is a mix of a high number of parallel requests, some lightweight like managing file status or listing directories, some transferring large data files, and some resulting in long delays like computing the checksum of a large file.

As my deployment was suffering from sparse errors, I was wondering if HTTP/3 could fix such issues.

HTTP/3 API mockup

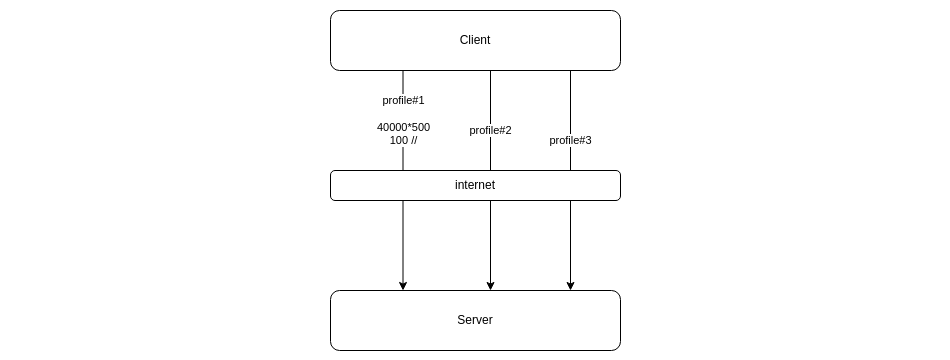

Before implementation and possible migration, I built a mockup to reproduce this kind of workload and being able to analyze it:

The mockup is written in Go and relies on the quic-go library. This library implements the QUIC protocol with all its extensions and the HTTP/3 protocol. WebTransport over HTTP/3 is provided on another repository by the same developer, Marten Seemann.

The mockup is simply a HTTP/1.1 or HTTP/3 client and server, generating in parallel different configurable load profiles.

The Go standard HTTP library and the quic-go library implementation of HTTP/3

offer a very clean separation between the application L7 HTTP services and the protocol implementation.

Switching from HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/3 is thus very simple and limited to the connection setup.

On the client side:

import (

"net/http"

"github.com/quic-go/quic-go"

"github.com/quic-go/quic-go/http3"

)

// ...

if isHttp3 {

// a RoundTripper is the view of a Transport protocol dedicated to HTTP needs

roundTripper := &http3.RoundTripper{

TLSClientConfig: tc,

QUICConfig: &quic.Config{},

}

hc = &http.Client{

Transport: roundTripper,

}

} else {

hc = &http.Client{

Transport: &http.Transport{

TLSClientConfig: tc,

},

}

}

// same HTTP API

hc.Post(url, "application/octet-stream", data)

On the server side:

func RunServer(config *Config, logger *slog.Logger) error {

// a Mux maps URL paths to functions handling the requests

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/",

func(writer http.ResponseWriter, request *http.Request) {

bytesRead, err := io.Copy(io.Discard, request.Body)

// ...

// ...

if isHttp3 {

err = http3.ListenAndServeQUIC(addr, config.CertFile, config.KeyFile, mux)

} else {

err = http.ListenAndServeTLS(addr, config.CertFile, config.KeyFile, mux)

}

The tests results on a WAN with 60ms latency and 1 Mbps average bandwidth is following:

- for a large number of small requests (< 1kB), we can exchange data twice faster, and the resulting data volume is a little bit smaller with HTTP/3

- for larger data sizes, no significant performance gain is observed with HTTP/3

- no error occur even under very high load, neither with HTTP/1.1 nor with HTTP/3

Not helpful concerning my use case, however the results are really impressive concerning highly reactive APIs.

Hosting a HTTP/3 API

As APIs handling a large number of small requests on WAN obviously benefit from HTTP/3 characteristics, the remaining point is their hosting. There are many solutions for hosting an API and we only briefly describe two of them, mainly to underline the important differences induced by HTTP/3.

Example with a reverse proxy

The hosting of an API must answer to several distinct but linked requirements and constraints:

- the security: TLS and authentication, certificates management

- the availability: load-balancing and failure recovery

- routing requests to backends

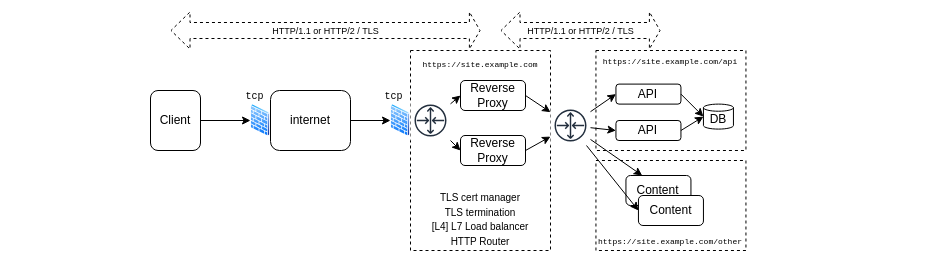

This would involve the basic building blocks if using HTTP version 1.1 or version 2:

With those standard components, switching to HTTP/3 is rather challenging:

First, UDP/443 traffic must be authorized both on the internet proxy for outgoing flows, not easy on many corporate infrastructures, and on the hosting platform for incoming flows, easier, but as we mentioned, QUIC is young and implemented as a library, so the Cybersecurity would look closely at it. Moreover, TLS inspection (what?) solutions generally won't support HTTP/3.

Many solutions exist to handle load balancing which can be implemented, when API calls are stateless, either at L4 or at L7 level. Managing L7 connections also enables hostname based routing or URL path based routing towards distinct backend services. Failure recovery may provide better availability at L7 level as it applies at the request level.

Such solutions may be implemented for HTTP/3 but support for self-hosting is yet limited:

- HAProxy supports both inbound and outbound connections

- Traefik only supports inbound connections

- Nginx only implements inbound connections as experimental

- Caddy also has reverse proxy features and supports inbound connections

So, except for HAProxy, the HTTP/3 connections will only come up to the proxy, but the backend will be accessed with HTTP/1.1 or HTTP/2 protocol. In any case, the TLS termination and the new connection to be established with the backend induce more latency.

Load balancing at L4 is also an option, so UDP in the case of HTTP/3.

Finally, it is required in most cases to support HTTP/1.1 or HTTP/2 as well, for compatibility reasons, but also concerning protocol discovery as clients don't know a priori if the server talks with HTTP/3. And also for HTTP01 ACME challenge for certificate generation that requires an unencrypted connection, which is not allowed with HTTP/3. To be noted though, DNS solutions exist to work around the two last issues.

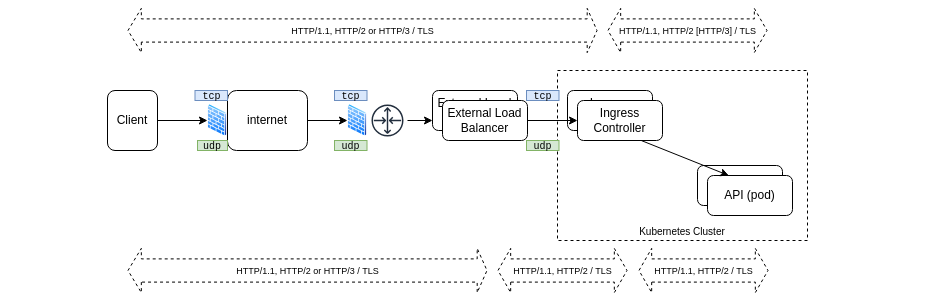

Example with Kubernetes

In the Kubernetes landscape, things are handled differently, with a high focus on availability when supported by protocols and applications, so rather working at L7 level than L4.

Depending on the infrastructure and on deployment choices, the HTTP connection may end either on the External Load Balancer or on the Ingress Controller. Switching to HTTP/3 will require to terminate it on the External Load Balancer, because the Ingress API does not support HTTP/3 yet.

An option can be to use UDP load balancing for HTTP/3 and leverage the new Gateway API.

Whatever the hosting solution is, a HTTP/3 termination will occur in front of the cluster, and it will add latency to a protocol that we want to use in cases where high reactivity is needed.

Conclusions

So the conclusion as far as APIs are concerned is really mitigated. We know that highly reactive APIs can really benefit from HTTP/3 but at the same time hosting solutions are either not mature or needing challenging adaptations, while loosing part of the performance gain.

Should we sleep until the solutions become more mature or stay awake?

Well, having a look at QUIC and HTTP/3 showed us that opportunities are real. New standards like WebTransport enable new kinds of Web Applications. We can also directly leverage the disruptive characteristics of the new QUIC transport protocol, using RPC and streaming interactions instead of HTTP APIs.

It is for sure for many of us a little bit early to push HTTP/3 APIs in production yet, but we may take actions to become more familiar with such solutions. So that such amazing technologies don't stay only the business of cloud giants.

Further information

- In depth analysis of the QUIC and HTTP/3 protocols

- Another very cool in-depth analysis of HTTP/3 in 3 parts Part1, Part2, and Part3

- Great information, though a little bit outdated, about the performance of HTTP and TLS (among others)

- HOL blocking

- QUIC applicability study

- Application (multimedia/video)

- A QUIC implementation in pure Go

And also: